Brief History of the San Antonio River Authority

The following information is a chronological look at the San Antonio River Authority’s (River Authority) history, from its inception in 1937 to the present day. A brief look into the future of the River Authority is also included at the end. To learn more about all of the River Authority’s current projects, please browse our website. If you’re interested in learning more about the River Authority’s 75 years of service to the communities of the San Antonio River Watershed, please visit the Institute of Texan Cultures, which is where the River Authority’s archives are housed.

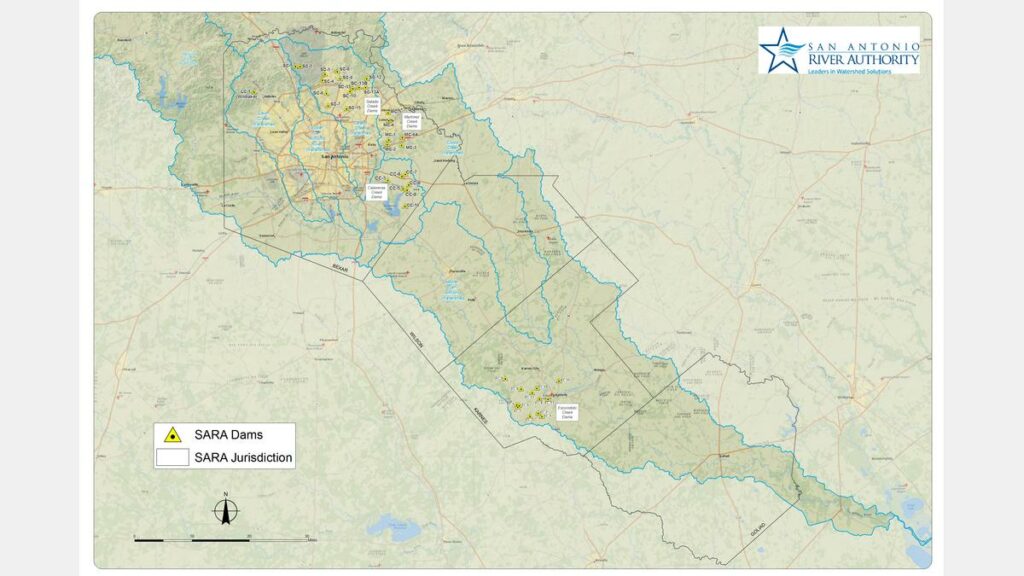

On May 5, 1937, the 45th Legislature of Texas created the San Antonio River Canal and Conservancy District. The members of original Board of Directors were all from Bexar County and they met for the first time on June 11, 1937. The focus of the newly created District was to plan a barge canal for commercial transportation of goods and materials by commercial barge between San Antonio and the Texas coast. The lack of feasibility for the canal project, combined with a devastating flood in San Antonio in 1946, changed the emphasis of the District from navigation to flood control. A San Antonio River Watershed Study was completed in 1952, which recommended the construction of approximately 85 dams throughout the basin.

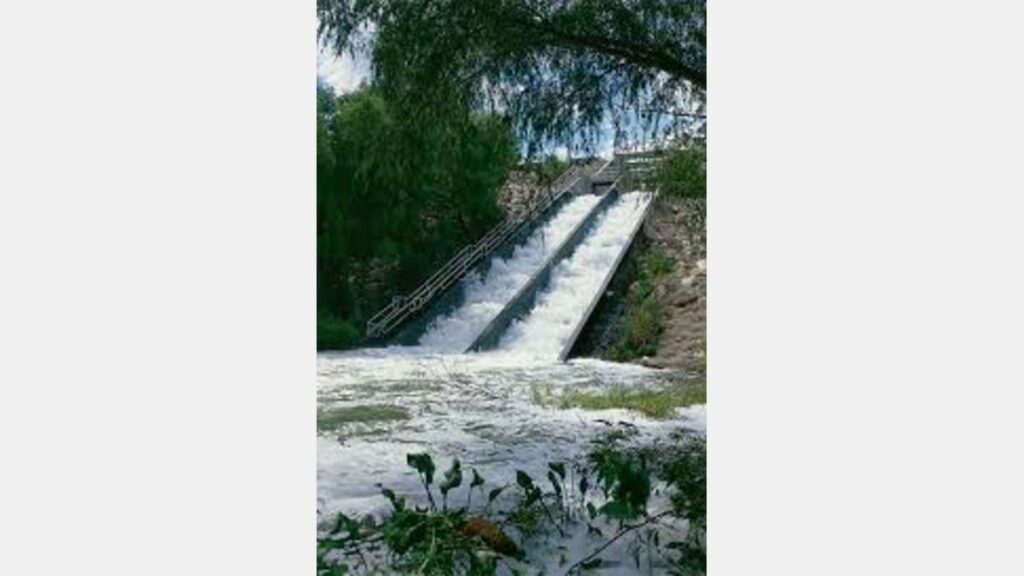

With a new focus on flood control, the District was renamed the San Antonio River Authority in 1953. The dams in the Calaveras Creek (Bexar County) and Escondido Creek (Karnes County) watersheds were two of only four such flood control projects funded in the entire State of Texas in 1953. In 1954, Congress authorized construction of the San Antonio Channel Improvement Project (SACIP), on which the River Authority served as local sponsor for this U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) project. Construction began on the SACIP in 1958. By 1959, nine dams along Calaveras Creek and eleven along Escondido Creek were completed and plans were underway for additional dams along Martinez Creek and Salado Creek (both in Bexar County).

In 1961, the River Authority was reorganized once again, adding all of Wilson, Karnes and Goliad counties to its jurisdiction, changing the Board of Directors to 12 members elected by the people (unique to Texas river authorities) and authorizing the levy and collection of an ad valorem tax capped at two cents per $100 valuation. While flood control remained a focal point of the River Authority’s activities, the additional tax revenue allowed the River Authority to initiate several new programs including water supply projects, water quality studies and sewage treatment projects. With these new funds, the River Authority was able to start the basin stream monitoring and surveillance program in 1962 – San Antonio River Authority stream monitoring is still going today.

Construction of the SACIP remained the focal point of the River Authority throughout the 1960s. A severe flood in 1965 led to the project boundary being expanded in 1967. In 1968, the King William section of the SACIP was completed, which garnered the Chief of Engineers’ 1971 National Award of Merit for General Landscape Development. By the end of the decade, the River Authority had advanced over half of the construction on the SACIP, constructed fifteen dams of the Salado Creek Watershed Project, completed the San Antonio River Basin Pollution Prevention Study (the first of its kind in the state), opened two wastewater treatment facilities and further expanded its mission by including recreation with an agreement to operate Braunig Lake and Calaveras Lake Parks.

Throughout the 1970s, the River Authority continued construction on the SACIP, with a focus on Alazan, Martinez, San Pedro, Apache and Six Mile Creeks. Additionally, the River Authority’s water quality activities increased dramatically based in part on some significant federal actions, including the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1970 and the 1972 amendments to the Federal Water Pollution Control Act (Clean Water Act). The River Authority’s increased water quality activities included not only efforts to protect surface water, but also to protect the Edwards Aquifer. From 1970-73, San Antonio River Authority successfully litigated against eight polluters in the basin, thereby establishing public awareness of the River Authority’s commitment to water quality. Furthermore, the River Authority became a signatory to the Texas Water Pollution Control Compact and adopted the Alamo Area Council of Governments’ (AACOG) Interim Regional Wastewater Development Plan for the upper basin in 1971.

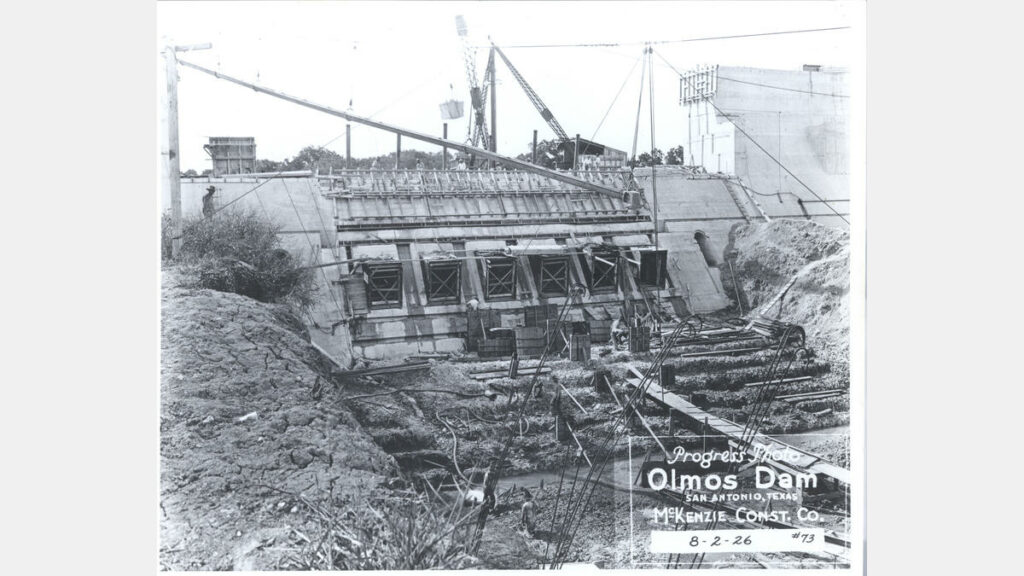

In 1973, the San Antonio River Corridor Study was completed, providing a conceptual plan for improvements along the San Antonio River from Hildebrand to I.H. 10 through downtown San Antonio – the study was a precursor to today’s San Antonio River Improvements Project (more information about the San Antonio River Improvements Project is found in the sections related to the 1990s to the present). The River Authority led an engineering study of the structural integrity and adequacy of Olmos Dam in 1974, and by 1979 headed construction of the dam modifications, which were completed in 1982. The River Authority’s Upper Martinez and Salatrillo Creek wastewater systems expanded in 1974. River Authority staff moved into their new main office and laboratory facility at 100 E. Guenther in San Antonio in 1975 – this building still houses the River Authority’s main office. From this new facility, the River Authority began providing laboratory analytical services to the Texas Water Quality Board and its successor, the Texas Department of Water Resources in 1976. Also in 1976, the River Authority worked with the City of Floresville to partially fund the Lodi Creek Drainage Project. Acting as a leader in water conservation, the River Authority enacted an Urban Water Conservation Program in 1979 requiring water-saving plumbing fixtures in all new development added to the River Authority’s sanitary sewer systems.

Throughout the 1970s, the River Authority constructed infrastructure and amenities for both Braunig Lake and Calaveras Lake Parks. Advancing additional parks and recreation activities, in 1979 the River Authority cooperated with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to add some public facilities to Goliad State Park and supported the initiation of planning by the National Park Service for the San Antonio Missions National Historic Park.

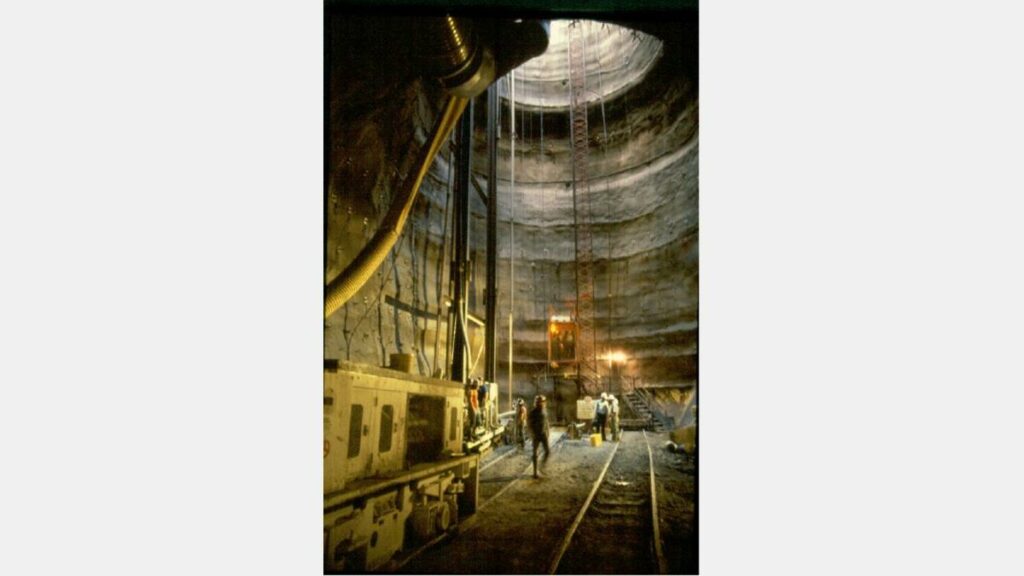

The SACIP continued into the 1980s with a focus on the development of by-pass tunnels to provide further flood control to downtown San Antonio – the concept was advanced in 1982 and preliminary designs were completed in 1985. While planning for the flood tunnels progressed throughout the 1980s, the multi-purpose Nueva Street Bridge, Dam and Marina Project was completed by the River Authority in 1987. Today this still serves as a critical part of the flood control and operations of the San Antonio River Walk.

Throughout the 1980s, the River Authority was active in water conservation and development, which included providing input to an Ad-Hoc Committee on Water Planning for the City of San Antonio (1981); helping establish the Xeriscape Project which demonstrated water conservation through selective landscaping with native plants and water-saving irrigation techniques (1985); participating in a technical advisory capacity in the “San Antonio Regional Water Resource Study” (1986); and completing the “Water Availability Study for the Guadalupe and San Antonio River Basins” (1986).

The River Authority’s regional water quality laboratory expanded services in the 1980s, as did the River Authority’s wastewater treatment plants. By the end of the decade, four additional dams were added to the Salado Creek Watershed Project, bringing the total number of dams operated and maintained by the River Authority to 13 in Karnes County and 25 in Bexar County. River Authority continued its support of the San Antonio Missions National Historic Park by conveying to the park several parcels of land adjacent to the San Antonio River to expand and enhance the newly created National Park. Recreational use, primarily fishing, at Braunig Lake and Calaveras Lake Parks also continued to increase throughout the decade.

The SACIP continued with the construction of the San Antonio River Tunnel Project, which was initiated in 1993 and completed in December 1997. Ten months later, on October 17-18, 1998, south central Texas experienced record-breaking rainfall, and the tunnels performed as designed, sparing downtown San Antonio from a devastating flood. In 1999, the tunnel project won the State of Texas Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award from the American Society of Civil Engineers; it also received a national-level Award of Merit. A year later, it was one of four projects to receive the Federal Design Achievement Award from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), as well as an achievement award from the American Society of Civil Engineers in recognition of the Tunnel Inlet Site.

Throughout the 1990s, SACIP work also continued on San Pedro, Alazan, Martinez and Apache Creeks. An additional dam was completed as part of the Salado Creek Watershed Project in 1996, and the final dam to be built within Salado Creek Watershed began construction 1998. Also in 1998, the River Authority authorized the creation of a local stakeholder group to be named the San Antonio River Oversight Committee (SAROC), whose purpose was to advise River Authority, the City of San Antonio (COSA) and Bexar County on planning, design, project management, construction and construction phasing and funding for the development of flood control and amenity improvements on what would become known as the San Antonio River Improvements Project (SARIP). SAROC

The mid-1990s also saw River Authority complete several water quality activities, including: a water quality study in the River Loop area for COSA; a multi-year partnership with the United States Geological Survey (USGS) to fund water quality and stream flow monitoring stations; a nonpoint source pollution pilot study with the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (TNRCC) and regional water quality studies (also with the guidance of TNRCC’s Clean Rivers Program); a Total Maximum Daily Load assessment on Salado Creek; and a biological study in the vicinity of Kelly Air Force Base.

Maintenance, improvement and expansion of the River Authority’s wastewater services continued to be a top priority in the mid-to-late 1990s, and the agency’s success was reflected by being awarded the 1995 EPA Region 6 Regional Administrator’s Environmental Excellence Award for Operation and Maintenance at the Martinez II Wastewater Treatment Plant. Additional wastewater service awards garnered in the 1990s included a National Award for Operation and Maintenance and the Regional Administrator’s Environmental Excellence Award in 1996, both from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Identification of potable water resources was a top priority for the River Authority and other public entities in the 1990s. As a result, the River Authority entered into various agreements, participated in studies or generally coordinated with numerous water agencies including the Edwards Aquifer Authority (EAA), Texas Water Development Board (TWDB), San Antonio Water System (SAWS), Bexar Met, Nueces River Authority, Lower Colorado River Authority (LCRA) and Guadalupe Blanco River Authority (GBRA). Passage of Senate Bill 1 by the Texas Legislature in 1997 led to the TWDB designating 16 regional water planning areas across the state; the River Authority district was included in the Regional Water Planning Group for Region L. In 1998, the River Authority was asked to serve as the administrative agency for Region L – a responsibility the River Authority continues to have today.

Activities pertaining to parks and recreation in the 1990s included: leasing River Authority property at two dam sites for recreational development; coordinating with the City of Converse to use the Martinez Site 4 as a city park; supporting COSA’s Open Space Planning efforts and Mission Trails Project; and constructing park road improvements at Braunig Lake and Calaveras Lake Parks.

In 2000, the River Authority was successful in obtaining Congressional approval to include environmental restoration and recreation as project purposes for SACIP (the 1954 federally authorized flood control project) – which opened the door for the development of the Mission Reach Ecosystem Restoration and Recreation Project as part of SARIP (the local plan conceived in 1998 to improve the river). The design for the downtown portion of SARIP was completed and a construction contract was executed in 2000; this section was completed in 2002, and was recognized with a historic preservation award from the San Antonio Conservation Society and the Downtown Alliance’s Downtown Best award for the Best Arts & Culture Project. The River Authority formed the San Antonio River Foundation in 2003, whose purpose is to raise private money to bring artistic, recreational, environmental and educational enhancements to the river. The newly formed foundation has been actively supporting SARIP since its creation. By 2004, design of both the Mission and Museum Reaches were nearing completion. In 2005, planning began for the Westside Creeks Restoration Project to restore San Pedro, Alazan, Martinez and Apache Creeks while continuing to improve flood protection for the area. In 2006, the USACE approved a project cooperation agreement to initiate the construction phase of the Mission Reach Ecosystem Restoration and Recreation Project. Construction of the Urban Segment of the Museum Reach began in 2007 and was completed in 2009. In 2010, the River Authority won the Downtown Alliance “Best of” 2009 award for the Best Public/Private Partnership for the Museum Reach. Construction of the Mission Reach began in 2008 and is scheduled for completion in 2013.

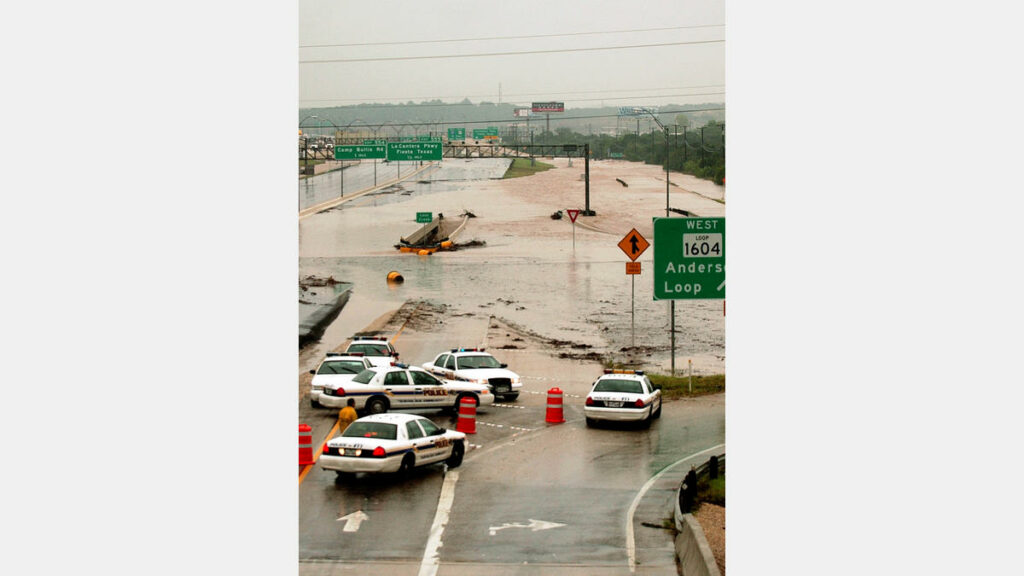

Following the devastating floods of 2002, the River Authority focused on another major flood control project related to Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) buyouts in the Cibolo Creek floodplain – this extended to the City of La Vernia, Kendall County (Comfort) and a subdivision in Bexar County by 2004, and Falls City, the City of Goliad and Goliad County by 2005. The 2002 floods also served as a catalyst for the creation of the Bexar Regional Watershed Management (BRWM) partnership which brings the River Authority together with COSA, Bexar County and 20 suburban cities within Bexar County to work cooperatively on water quantity and quality issues. The final dam within Salado Creek Watershed Project was completed in 2004, and dam rehabilitations in the Martinez Creek and Salado Creek watersheds were completed in 2005 and 2007. Beginning in 2006, the River Authority worked with FEMA to update and convert Bexar County flood maps to a digital format. The River Authority proceeded to take the lead in creating the new digital flood insurance rate maps (DFIRMs) for the entire River Authority District, which resulted in some of the most detailed DFIRMs in the nation becoming official in 2010. In 2008, Bexar County Commissioners Court approved a Flood Control Capital Improvements Program – through the BRWM partnership, the River Authority provided the county technical assistance with the planning for capital improvement program and real estate acquisition services for the program.

Water quality programs that had been developed in the 1990s continued to expand throughout the 2000s, adding the following projects: a biological survey of the San Antonio River to assess the risk of ecosystem stress resulting from groundwater contamination possibly related to area military activities; a wastewater monitoring and laboratory analyses project associated with a research study on restaurant wastes; a baseline fish population inventory near the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park; a watershed protection plan for SARIP for the purpose of describing targeted water quality issues, pollutants, nonpoint source pollution management measures and a schedule for their implementation; and a River Loop water quality and flow study. On a basin level, the River Authority became the lead agency to conduct a total maximum daily load assessment project to address dissolved oxygen and fecal coliform bacteria problems. The River Authority conducted a water quality monitoring and laboratory analyses project associated with a bacterial survey of the lower San Antonio River and development of a network of remote water quality monitoring stations throughout the river basin. The water quality monitoring activities associated with the Clean Rivers Program continued, as did the River Authority’s cooperative project with USGS for operation and maintenance of stream flow monitoring stations. The River Authority also conducted an instream flows study and a fish community sampling study in the lower basin. The increase in tasks related to execution of the various contracts placed a significant load on the River Authority lab, which experienced not only expansion but investment in state-of-the-art equipment during the first decade of the twenty-first century. In 2007, the Environmental Sciences Department Laboratory held its grand opening, and a few months later, the lab received National Environmental Laboratory Accreditation.

As Bexar County experienced significant population growth, the River Authority responded by improving and expanding its wastewater treatment services. Numerous requests came to the River Authority for wastewater treatment services within Bexar County and in adjoining counties, and we responded by conducting regional wastewater facilities studies and assessments of cities and unincorporated areas in Bexar, Wilson, Karnes and Goliad counties. The River Authority went on to either take over or offer assistance to numerous wastewater facilities in smaller communities throughout the basin. In 2009, the River Authority Utilities Department and the City of Somerset received the Water Environment Association of Texas Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant of the Year Award.

With regards to potable water planning, the River Authority continued its administrative role with Regional L, and entered into an agreement with SAWS and GBRA to secure the under-utilized portion of those water rights as a raw water supply for 50 years. When this agreement with SAWS and GBRA was terminated, the River Authority continued its involvement with a larger leadership role by agreeing to complete the Whooping Crane and Estuary Responses Project joint studies. The River Authority’s involvement with water supply issues in the downstream counties was an important part of the agency’s basin-wide program, including: entering into agreements to help provide potable water and sewer service to the citizens of Berclair and Fannin in Goliad County; providing grant funds for construction of the Cologne water system in Goliad County; joining Kenedy in Karnes County to submit a joint TWDB grant application to improve and upgrade the city’s desalination facilities; and as a public service, purchasing the Calico Water System in Wilson County that provided water service to three subdivisions. By 2005, the River Authority began to take steps to acquire water rights by purchase to help ensure adequate environmental flows in the river. Throughout the 1990s, the River Authority was involved in discussions about how best to balance the use of Edwards Aquifer water for drinking with the need to provide flows to Comal and San Marcos Springs. In 2006, the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) brought together a group of stakeholders, which included the River Authority, to participate in a regional, collaborative process to develop a plan to contribute to the recovery of the federally-listed species dependent on the Edwards Aquifer. This stakeholder process became known as the Edwards Aquifer Recovery Implementation Program (EARIP), and the River Authority has had a significant role in the EARIP from its inception through the present.

The River Authority remained committed to the recreational opportunities offered by the facilities at Braunig Lake and Calaveras Lake Park; however, in 2008, the River Authority amicably ended its 40-year relationship with CPS Energy to operate the lake parks in order to pursue other types of recreational properties throughout the basin. Other initiatives associated with parks and recreation activities occurred in southeastern Bexar County and in Wilson and Goliad counties within a context of basin-wide planning led by the River Authority. One of the first new recreation projects was an interlocal agreement with Wilson County for the development, operation and maintenance of Jackson Nature Park, a 50-acre tract on Cibolo Creek that had been donated to the county in 1999. In 2003, a regional park planning advisory committee was created which was tasked with providing community outreach and oversight to staff and consulting planning for an integrated regional network of nature-based park resources. Phase I of the Regional Park Planning Advisory Committee report was completed in early 2005, and Phase II was approved in late 2005. In 2006, the River Authority adopted Phase II of the San Antonio River Basin Plan for nature-based park resources, and established a Regional Park Coordinating Council to provide a forum for organizations involved in the plan. By 2007, the River Authority opened the Goliad Paddling Trail, its first officially designated paddling trail, and in 2009, the River Authority purchased nearly 100 acres of land along the San Antonio River in Wilson County to be known as the Helton San Antonio River Nature Park.

Growth in the number and complexity of programs administered by the River Authority in the first decade of the 21st century was made possible, in part, by the many interlocal agreements we executed with other agencies and by the board’s decision to reinstitute the ad valorem tax on property within the four-county river basin beginning in the tax year 2002.

Construction of the SARIP Mission Reach Project continued with groundbreakings for Phases 2 and 3 of the project taking place in 2010. Phase 1 of the Mission Reach opened at the end of 2010 while Phase 2 opened in 2011. At the grand opening of Phases 1 and 2 of the Mission Reach, Department of the Interior Secretary Ken Salazar claimed that the Mission Reach Project was leading the nation in urban ecosystem restoration as he publicly supported the World Heritage Site Nomination of the San Antonio Missions National Historical Park – a nomination process that the River Authority continued to actively support through the Missions’ inscription on July 5, 2015. Additional portions of the Mission Reach Phase 3 opened in 2012, including the first section of the Mission Reach that was accessible to paddle recreation. The Mission Reach Project, along with the Museum Reach which is north of downtown, were completed by the end of 2013.

Additional rehabilitation work on the dams operated and maintained by the River Authority was authorized in 2010, 2011 and 2012. The River Authority also took the lead on dam rehabilitation work outside its District when it agreed to oversee the work being done to the Medina Dam – that work was completed in 2012. From the late 2000s through 2012, the River Authority continued to work to leverage the DFIRM investment, both locally and with the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). This leveraging includes: The River Auhtority’s role as a Letter of Map Revision (LOMR) Delegation Partner with FEMA; the River Authority’s roles in FEMA’s RiskMAP program and recent mapping updates; the River Authority’s role with Emergency Operations Center on the Flood Alert System for Bexar County; the River Authority’s recent update of the downstream flood warning system; and the River Authority’s development of holistic watershed master plans.

San Antonio River Authority’s wastewater service continued to receive honors, winning the Water Environment Association of Texas 2010 Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plant of the Year, which went to the Salatrillo Plant and the River Authority’s Utilities Department. Work continues on a new wastewater treatment facility in Bexar County known as the Martinez IV wastewater system. Additionally, an agreement was signed with the Alamo Community College District for the River Authority to provide permitting, project management, construction and ongoing operations and maintenance services for a new wastewater treatment plant at the ACCD First Responders Academy Campus, which is set to begin construction in 2012.

From the late 2000s through 2012, the River Authority has been involved with a number of water quality projects including: the administration and development of a total maximum daily load implementation plan for the upper San Antonio River and Salado and Walzem Creeks; the River Walk Implementation Project in the River Loop area; an agreement to conduct water quality surveys on Leon Creek as part of the Leon Creek total maximum daily load program; administration and conducting of water quality monitoring activities in accordance with the Clean Rivers Program; providing water quality modeling services for the Texas Instream Flows Program and Lower San Antonio River Instream Flow Study; undertaking total maximum daily load related projects in the San Antonio River Watershed; revising and updating of the Upper San Antonio River Watershed Protection Plan; and continuing long-standing water quality studies with the USGS.

Relating to both water quality and quantity; the Guadalupe, San Antonio, Mission and Aransas Rivers and Mission, Copano, Aransas and San Antonio Bays Basin and Bay Expert Science Team (BBEST) and Basin and Bays Area Stakeholder Committee (BBASC) submitted their recommendation reports in 2011. San Antonio River Authority has actively participated in both committees with the River Authority’s General Manager chairing the BBASC and an executive team staff member being appointed as a voting member of the BBEST. Additionally the River Authority provided administrative support to both committees to assist in meeting the Legislature’s strict deadlines. In 2012, the EARIP stakeholders submitted a plan for approval to the FWS, and the River Authority’s role in the EARIP process expanded as the River Authority took on the responsibility to acquire 40,000 acre/feet of water in support the EARIP plan.

With development of the Eagle Ford Shale oil and gas fields underway by 2009, the River Authority became involved in a number of issues related to the burgeoning oil and gas exploration and development. Given the River Authority’s ownership of the bed and banks of the San Antonio River and its tributaries, conveying easements across the San Antonio River and its tributaries to oil and gas companies and conducting onsite monitoring of the construction of the pipeline quickly became a role the River Authority played in the Eagle Ford Shale development. The River Authority also amended its surface water rights permits for irrigation use in Bexar, Wilson, Karnes and Goliad counties to add the purposes of environmental flow, recreation and pleasure, public parks, navigation, game preserves and industrial and mining uses. The new permitting requirements allowed the River Authority to lease surface water rights, which incorporate instream flows protections, to oil and gas companies and use the fees to fund environmental investigations and studies in the lower basin. Continuing its work with oil and gas companies, the River Authority provided information to the private sector companies on issues related to hydraulic fracturing (e.g. visiting well sites to suggest ways to make site more environmentally sound with regards to onsite detention). Additionally, the River Authority started working more closely with County Floodplain Administrators to develop a checklist of best management practices that are need to obtain permits for oil and gas sites being developed in the floodplain. In 2011, the River Authority organized a multi-agency summit to bring all the different regulators together in order to share information and develop contacts with each other. The River Authority also began working with the USGS in a Lower San Antonio River study of chemicals typically used in the hydraulic fracturing process to establish a baseline – future monitoring of chemicals will use this baseline to determine if more/less chemicals are found in the San Antonio River.

Furthermore, the River Authority installed a USGS water quality gauge at Highway 72 and the San Antonio River to monitor any changes in water quality. The River Authority will continue to fund the operations and maintenance of the gauge. Continuing its outreach to the local communities most impacted by the growth of the Eagle Ford Shale Play, the River Authority began hosting community workshops in 2012 to educate community officials, staff and citizens and various topics. The River Authority also started developing an ordinance booklet in 2012 for lower basin communities to use as a template to update land use regulations (e.g. how to better manage the growth of trailer parks and the use of septic systems or improve development standards to minimize stormwater runoff concerns). Taking a long-term view of the Eagle Ford Shale development, the River Authority began promoting the donation of surface water rights by the oil and gas companies when the water rights are no longer needed for shale development – these donated water rights will be used to aid in environmental flows protections. Additional long-term planning by the River Authority included promoting conservation easements to area land owners to protect their land in perpetuity. Finally, in cooperation with the San Antonio River Foundation, the River Authority is working to educate oil and gas companies on opportunities to support various river related parks, education programs and environmental studies throughout the basin with philanthropic contributions or by other means.

Beginning in 2011, the River Authority started spearheading discussions with the lower basin municipalities and counties regarding the formation of a Regional Watershed Management partnership (similar the Bexar Regional Watershed Management partnership we helped to create in Bexar County back in 2003). By the end of 2012, the new Regional Watershed Management partnership, formed by individual county, as it is in Bexar County. The southern basin Regional Watershed Management partnership provides a forum for regional discussions related to numerous watershed related issues, including the implementation of the recommendations being developed in the River Authority’s watershed master plans.

Recreational opportunities continued to blossom in 2011 with the opening of the Branch River Park in Goliad. More recreational opportunities were added to the area in 2012 with the opening of the initial phase of the Helton San Antonio River Nature Park in Wilson County and the Saspamco Paddling Trail running from southern Bexar County into Wilson County. In 2012, the River Authority also began planning for a new linear creek trail system in Kenedy running along the Escondido Creek.

For many, environmental sustainability means conserving energy and water, recycling or reducing air pollution. All of these things are essential in creating a healthy environment that can be sustained for generations to come. However, maintaining clean and healthy water in our creeks and rivers is also an essential element of environmental sustainability. How we care for our watershed now will determine the health of rivers and streams for future generations to enjoy. But, a sustainable watershed is not just good for the environment. In the long run, it will save taxpayer money through reduced stormwater infrastructure costs and operations and maintenance expenses. It will also improve the quality of life in our watershed through increased green space and landscape beautification.

The River Authority will continue to be a leader in promoting sustainability throughout our District. Some of the sustainability projects to be conducted by the River Authority beginning in 2020 and proceeding into future years include: a stormwater audit of the River Authority’s facilities; two sustainable projects – a rain garden and an erosion control project – at the River Authority’s Environmental Center, a stormwater improvement project at the River Authority’s main office and the development of a new maintenance facility has been constructed in support of the Mission Reach Project all using best management practices (BMPs) and will serve as demonstration projects for the community; development of a triple bottom line tool that will assist in the decision-making process to determine the best sustainable capital improvement projects to implement; the offering of sustainability training for both in-house and external audiences; and the creation of a Low Impact Development (LID) Competition to promote this type of development throughout the larger San Antonio community.

The River Authority’s core values of Accountability, Excellence, Open & Direct Communication, and Team Work & Collaboration permeates all our decisions. Our governmental and community partners value the River Authority’s opinion on issues because we strive to make decisions based on the best available information or data. Science, be it environmentally-based or engineering, is the foundation of service that the River Authority provides the community, and that will continue on into the future. Conducting water quality monitoring, laboratory and field activities and environmental investigations will all continue. Developing and maintaining holistic watershed master plans, completing and implementing the Flood Alert system and continuing the River Authority’s partnership with FEMA will be a significant part of our future. Providing award winning service at our wastewater treatment plants will continue, as well as providing wastewater assistance to the smaller communities throughout our District. Growing nature-based recreational opportunities will also continue to be a focus for the River Authority. Of course, completing the San Antonio River Improvements Project in 2013, finishing the tree plantings along the Mission Reach in 2015 and continuing to maintain the Museum Reach, Eagleland and Mission Reach segments of the San Antonio River Walk will be an ongoing priority for the River Authority. Moving the Westside Creeks project forward from vision, through planning and into construction will be a River Authority focus for years to come.

This is just a snap shot of where River Authority is today and the direction it is moving towards. River Authority staff is passionately committed to the preservation, protection and sustainability of the San Antonio River Watershed. We are accountable to the Board of Directors, citizens, stakeholders and partners of the communities we serve. The River Authority will continue to base decisions on prudent financial management and sound scientific/engineering principles and practices, and we remain committed to taking collaborative, adaptive and strategic actions that address watershed issues and priorities. It has been a pleasure to serve the citizens of Bexar, Wilson, Karnes, and Goliad counties for the past 83 years, and we look forward to providing great and responsible service for years to come.

Cultural History

The San Antonio River Basin is home to rich and varied cultures. Payaya, Coahiltecan, Karankawa, Lipan Apache and Tonkawa Indians; Spaniards; Mexicans; American settlers from the east; and German, Czech, and Polish immigrants are among the early peoples who shaped and settled the San Antonio River Basin. Plentiful water drew them to the basin, where their various cultures took root and still influence communities, traditions, festivals and events.

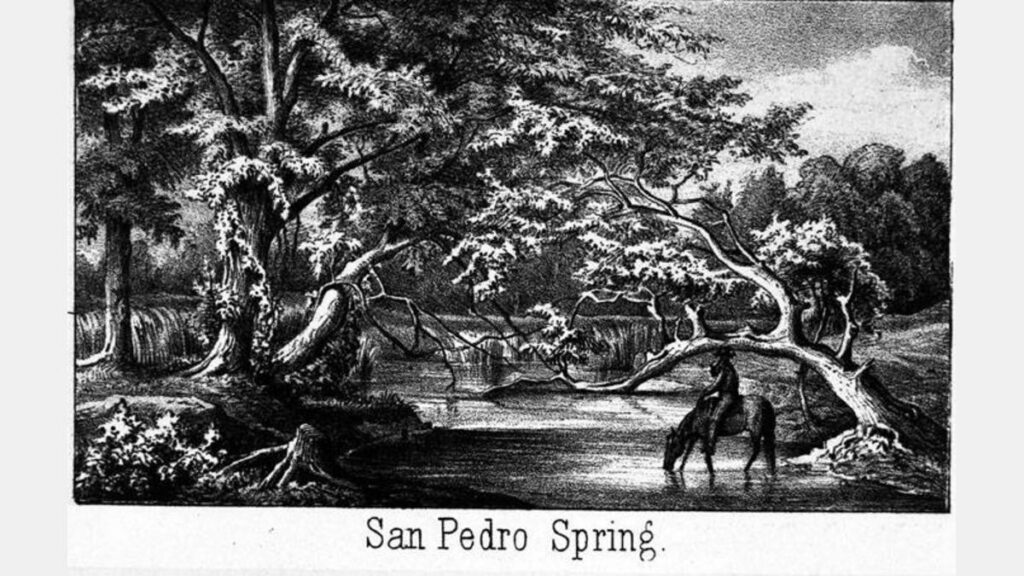

Before the Europeans

The headwaters of the San Antonio River were a gathering place for Native Americans over 12,000 years ago, providing precious water in a semi-arid landscape and attracting game. When the Spanish made an expedition in 1691, they found an encampment of Payaya Indians beside a river they called Yanaguana. Other Coahiltecans, along with Karankawas, Lipan Apache, and Tonkawa hunter-gatherers, led a nomadic life throughout the river basin, gathering mesquite beans, prickly pear fruit, pecans and other wild plants and hunting deer, bison and smaller mammals, as well as taking fish from the river itself.

The Spanish

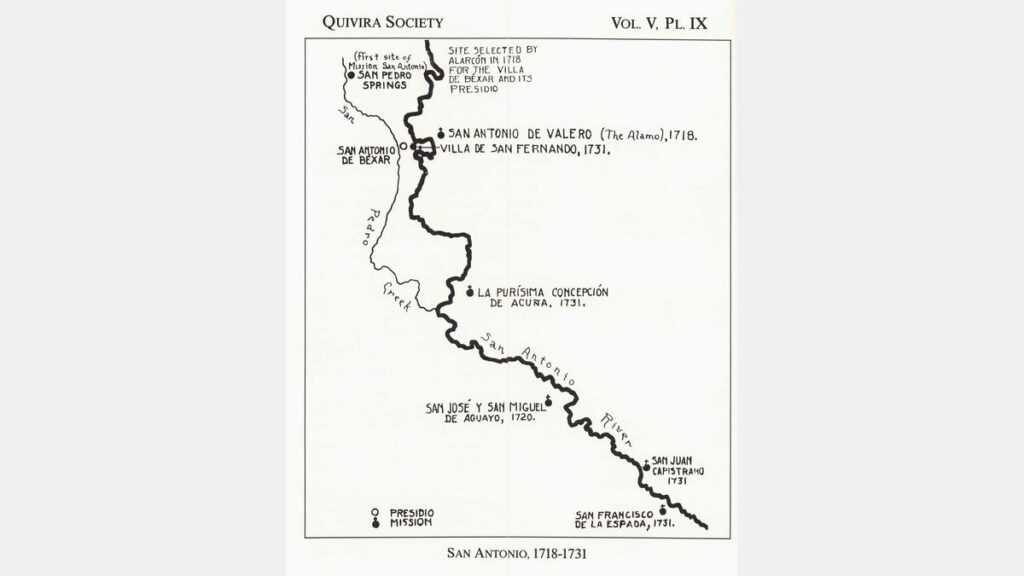

The San Antonio River was also a lifeline for the next wave of human habitation. The Spaniards established presidios (forts), civil settlements and missions along the river in Bexar, Wilson and Goliad counties and associated ranches in Medina, Bexar, Atascosa, Wilson, Karnes and Goliad counties. These ranches provided cattle, horses, goats and sheep to the missions.

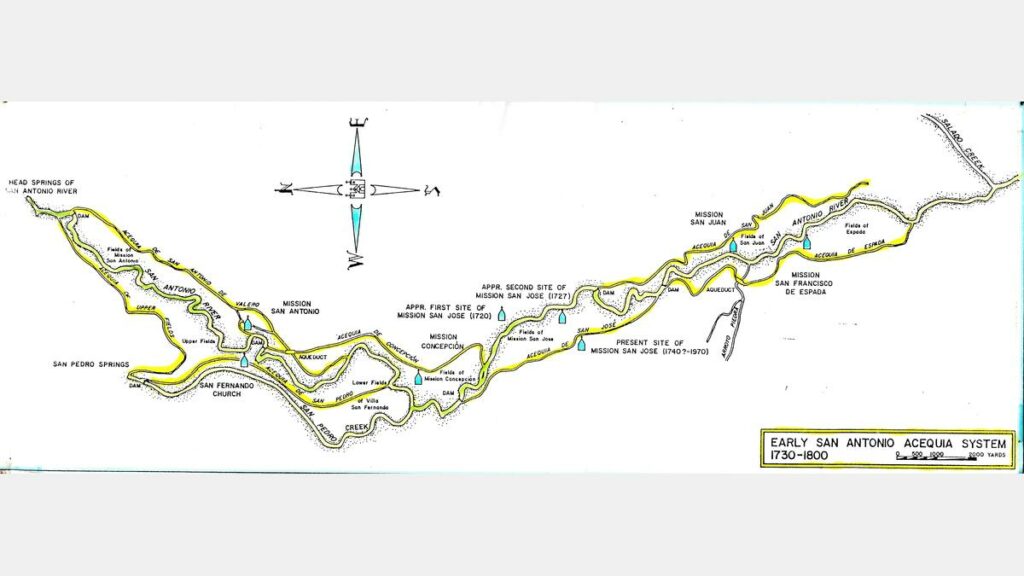

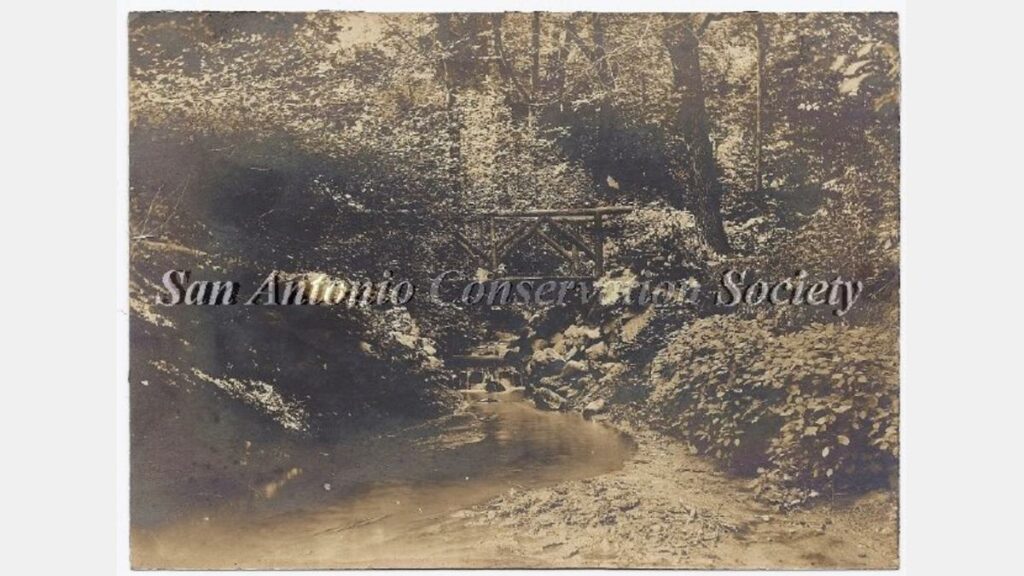

The missionaries and their Indian laborers tapped the San Antonio River for irrigation, building a system of acequias that watered corn and bean fields.

Acequias (irrigation ditches) had been in use in the arid parts of Spain since the 8th Century, so Spanish missionaries knew just how to route San Antonio River water into dry fields. The acequia associated with Mission Concepción was said to be large enough to be navigable by small boats! Mission Espada’s acequia system includes a stone aqueduct that is considered the oldest still in use in the United States.

In addition to the river, La Bahia Road, which is the southern section of the great Camino Real or King’s Highway, connected the missions and stretched about 700 miles from Monterey, Mexico to Louisiana. Today, state highways 181 and 239, and farm-to-market roads 887, 2043 and 81 parallel parts of the old road.

European Settlement

Fertile soil, open range, and the San Antonio River continued to attract settlers from Nueva España in the 1700s, followed by settlers coming west from the United States in the early 1800s. German, Czech and Polish immigrants established tight-knit farming communities throughout the area, including the first organized Polish settlement in the United States: Panna Maria in Karnes County. As the 19th Century progressed, so did the river basin. Railroads were built, more settlers arrived and large-scale agricultural production began.

Bexar County

The headwaters of the San Antonio River are in Bexar County, and the River is the reason for the area’s early settlement. Spanish soldiers established a presidio in 1716, making the first civil settlement possible in 1731. From 1718 to 1731, the missionaries established their five compounds and acequias to convert the Indians to Christianity and an agricultural way of life. When the first Anglo-Americans arrived in 1821, the little town of San Antonio de Béxar was home to about 2,000 Mexican colonists and soldiers. In the 1830s the battle for Texas independence from Mexico began, marked by the fall of the Alamo in 1836 and ending with the defeat of Santa Anna at San Jacinto that same year. After Texas became a state in 1845, the number of European and Anglo settlers increased dramatically and the county’s population and economy accelerated. Today, San Antonio is the 7th largest city in the United States and its colorful history, charming River Walk and missions make it a popular tourist destination.

After Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, the new government began secularizing the missions. Most mission property was distributed to the Indian inhabitants or sold to private parties by 1794. However, Mission Espíritu Santo remained in Franciscan hands until 1830.

Missions

BEXAR COUNTY

est. 1718

Mission San Antonio de Valero (The Alamo)

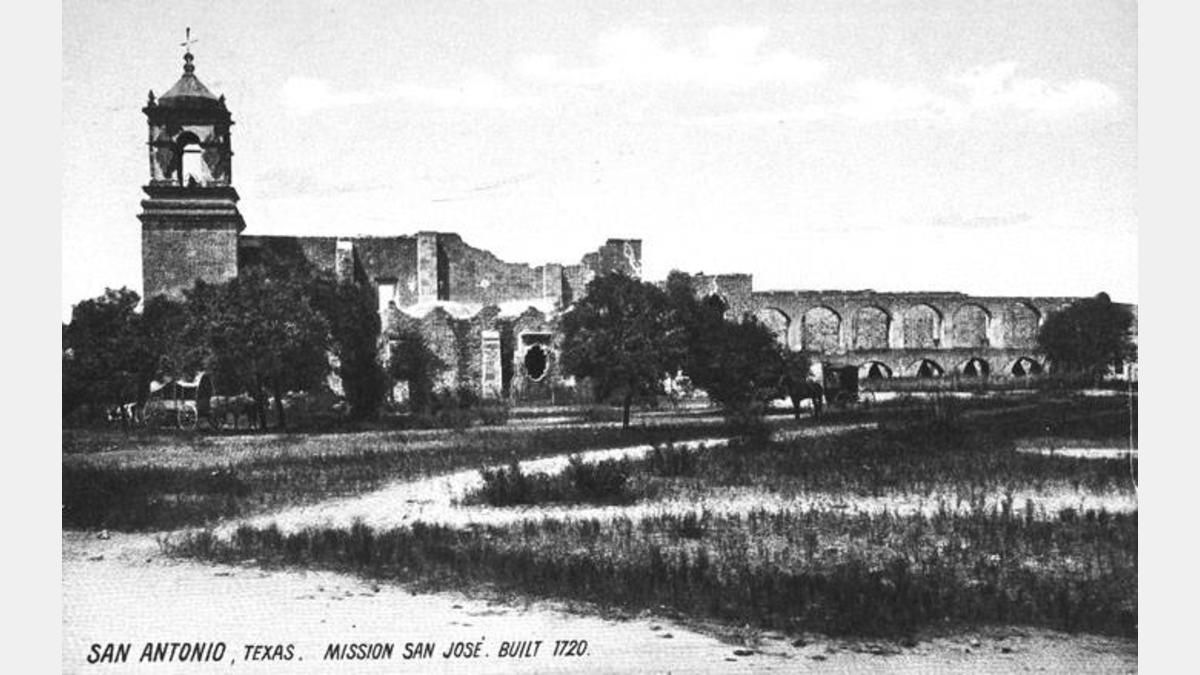

est. 1720

Mission San José & San Miguel de Aguayo

est. 1731

Mission Nuestra Señora de la Concepción

est. 1731

Mission San Juan Capistrano

est. 1731

Mission San Francisco de la Espada

WILSON COUNTY

est. 1731

Rancho de las Cabras

GOLIAD COUNTY

est. 1749

Nuestra Señora de Loreto Presidio (La Bahía)

est. 1749

Mission Nuestra Señora del Espíritu Santo de Zúñiga

Wilson County

When the Spanish established the chain of missions along the upper San Antonio River, they also established ranches to supply cattle, goats, sheep, mules and horses to the missions. Many of those ranches were in the area now known as Wilson County, where ranching is still a major part of the economy. Anglo-American, German and Polish settlers began arriving in the 1850s and an act of the Texas legislature established Wilson County in 1860. After the courthouse burned in 1883, county officials hired the noted architect Alfred Giles to draw up plans for the present-day courthouse in Floresville. Today Wilson County is a leading producer of peanuts and, in the industrial arena, provides oil and gas field services and produces structural clay products and fabricated metal plate work. Tourists visit Jackson Nature Park near Stockdale, the historic Brahan Masonic Lodge in La Vernia, the Dewees Remschel House near Poth [by appointment], the Wilson County Jailhouse Museum in Floresville, the National Park Service’s Rancho de las Cabras and the history exhibit at the Catholic Church in Kosciuszko.

An 18th Century Supermarket

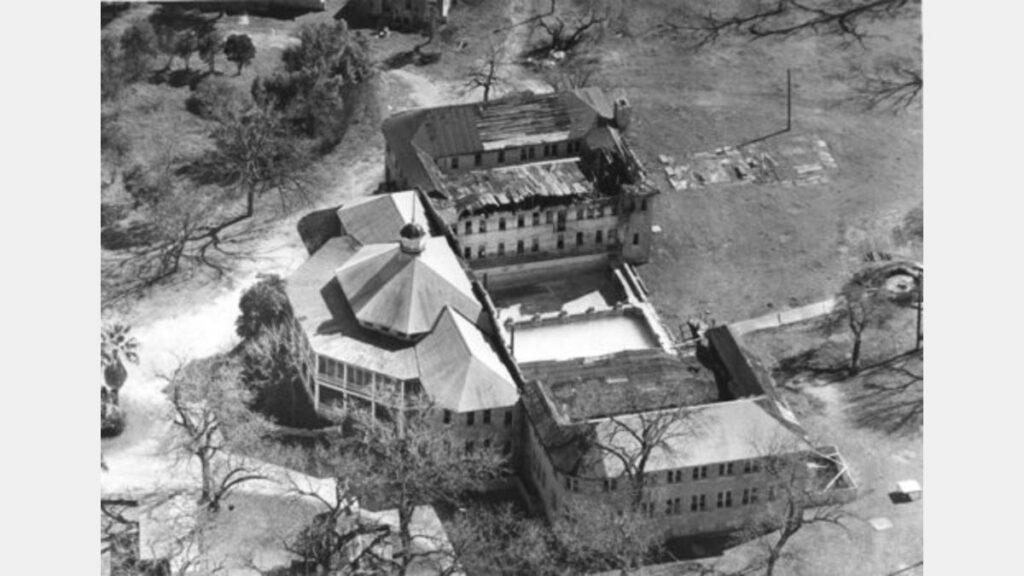

Rancho de las Cabras (Goat Ranch) belonged to Mission Espada. It provided the Franciscan friars and their Indian converts with horses, burros, cattle, sheep, pigs and goats from 1731 to about 1794. Today, all that remains of the Rancho’s stone perimeter wall and chapel are some foundation ruins that can be seen where Picosa Creek flows into the San Antonio River.

Karnes County

In the late 1700s, rich land in this area and the San Antonio River’s reliable water source led to the establishment of big ranchos, which became targets for raiding Comanches. Despite the presence of a fort, Fuerte de Santa Cruz del Cibolo, at Carvajal Crossing on Cibolo Creek, continuing attacks forced the abandonment of many ranches. By the 1850s Indian raids were in the past and Anglo Americans began settling the area, along with Polish immigrants who founded Panna Maria, the oldest Polish settlement in the U.S. Helena became the county seat when Karnes County was established in 1854.

The original courthouse still stands in old Helena, but today Karnes City is the county seat, presiding over a prosperous county with an economy based on ranching, agriculture and, until the early 1990s, uranium mining and processing. Tourists visit the historic churches of Czestochowa, the “painted church” and museum at Panna Maria, Old Helena and the city park and historic bandstand at Runge.

Goliad County

Evidence of Spanish settlement in the Goliad County area is preserved in the beautifully restored Mission Espíritu Santo and, across the San Antonio River, Presidio La Bahía. In the late 18th Century, the Franciscan missionaries converted and “civilized” the native Aranama and other Indians. The Presidio protected the mission and La Bahía Road, a vital trade route. During the Texas Revolution, the Goliad area witnessed history, including the drafting of the Goliad Declaration of Independence in 1835, the surrender of James Fannin’s forces at the Battle of Coleto and the subsequent infamous execution of the Texan prisoners. Goliad County is one of the 23 original counties established by the Republic of Texas in 1836. Today, farming and ranching is important to the county’s economy, and oil and gas production have also become major sources of revenue. The county attracts tourists to Goliad State Park, Mission Espíritu Santo, Presidio La Bahía, the historic Courthouse Square, General Zaragoza’s birthplace, Fannin Battleground State Historic Site and the Berclair Mansion.

San Antonio River Improvements Project

The San Antonio River Improvements Project (SARIP) was a $384.1 million investment by the City of San Antonio, Bexar County, San Antonio River Authority, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the San Antonio River Foundation in flood control, amenities, ecosystem restoration and recreational improvements along 13 miles of the San Antonio River from Hildebrand Avenue south to Loop 410 South. The River Authority served as project manager for all sections of the SARIP and as local sponsor with USACE specifically for the Mission Reach.

The SARIP was comprised of four distinctive reaches: The Museum Reach, a four-mile segment of the river from Hildebrand Avenue south to Lexington Avenue; the Downtown Reach, a segment of the original River Walk from Lexington Avenue to Houston Street; the Eagleland, a one-mile segment from South Alamo to Lonestar Boulevard; and the Mission Reach, an eight-mile section of the river extending from Lonestar Boulevard south to Loop 410 South.

A concerted community effort to revitalize the river began in 1998 when Bexar County, the City of San Antonio and the River Authority created the San Antonio River Oversight Committee. The 22 civic and neighborhood leaders appointed to the committee were given the responsibility of overseeing the planning, design, project management, construction and funding necessary to complete the project. In addition, the committee was charged with providing an open public forum for citizen input into the project’s development. The Oversight Committee was co-chaired by former mayor Lila Cockrell and architect Irby Hightower and an appreciation ceremony took place on November 2014 to commemorate the work of all the committee and sub-committee members throughout its existence.

Benefits of the Project

The main goals of the SARIP were restoring the ecosystems around the river and linking together access to the cultural institutions of San Antonio with a linear park, extended barge access, and improvements to over 15 miles of trails. These enhancements to the river encourage economic development, connect the communities of San Antonio, and provide space for people to enjoy recreational activities such as cycling, jogging, wildlife viewing, and access to paddling the river.

During the 1920s-1960s, the river was channelized to assist in flood mitigation. This helped move water faster through the system, but the removal of native vegetation and river features had negative effects on the wildlife of the San Antonio River.

The SARIP utilized hydraulic modeling of rain events to analyze the amount of native vegetation that could be planted for restoration without interfering with the efficiency of flood water conveyance. The ecosystem restoration was accomplished by rebuilding natural river features and planting native grasses, trees, and plant life near the river’s edge. These native plants provide habitat and food for many species of animals that have historically called the San Antonio River home. Additionally, the roots of these native plants grow much longer than traditional turf grasses found around residential areas. The long roots play an important role in bank stabilization by reaching deep into the soil to prevent erosion. This barrier of grasses and plants also serves as a filter for the stormwater flowing to the river after rain events, catching trash and filtering out pollutants from the runoff.

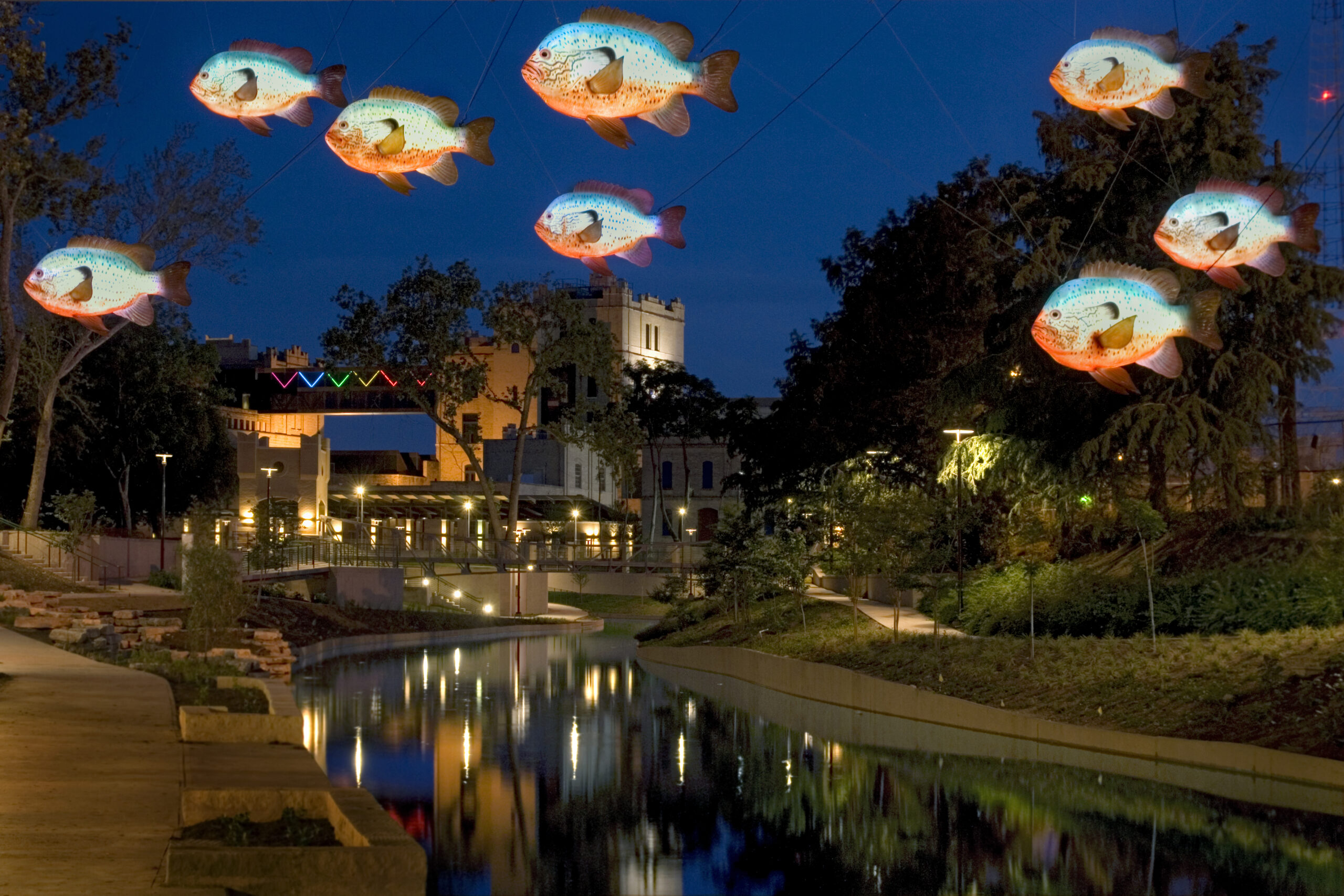

museum reach

San Antonio’s world-renowned River Walk, a top tourist destination in the state of Texas, doubled in length with the opening of the Museum Reach – Urban Segment. The new trails allow people to experience a previously undeveloped section of river north of downtown. Other additions include extended river barge access,landscaping, overlooks, boat landings, lighting, and water features. When added to the original River Walk, the completed project created a linear park through the heart of the city that is over 15 miles in length and is associated with over 2,000 acres of public park land. The new walkways provide easier access to historic parts of San Antonio such as the Museum of Art, the Pearl, the Witte Museum, Brackenridge Park, the San Antonio Zoo, and VFW post 76, the oldest VFW Post in Texas. Public art displays are also visible along the path thanks to donations raised by the San Antonio River Foundation.

The Museum Reach – Park segment includes constructed wetlands and enhancements to Acequia Madre near the Witte Museum, where wildlife can be viewed while walking along the two new pedestrian bridges crossing Brackenridge Park.

EAGLELAND SEGMENT

The Eagleland project is located along approximately one mile of the river just south of downtown San Antonio that had previously been channelized to aid in floodwater conveyance. Major components of the project include restoring ecological functions and values to the riparian corridor as well as improving recreational features. The restoration on this segment includes approximately 17 acres of river right-of-way, most of which was planted with native grasses, wildflowers, trees and shrubs beginning in 2006.

The San Antonio River Authority maintains the area through short and long term landscape management techniques to establish a diverse and native plant dominated community. This is a big challenge within the Eagleland Segment primarily because of invasion by non-native plants coming into the area from the existing seed bank as well as upstream and surrounding areas. The increased coverage by the native plants has led to numerous observations of wildlife utilizing the area. The River Authority continues to manage the area through appropriate herbicides and physical removal of invasive species.

MISSION REACH

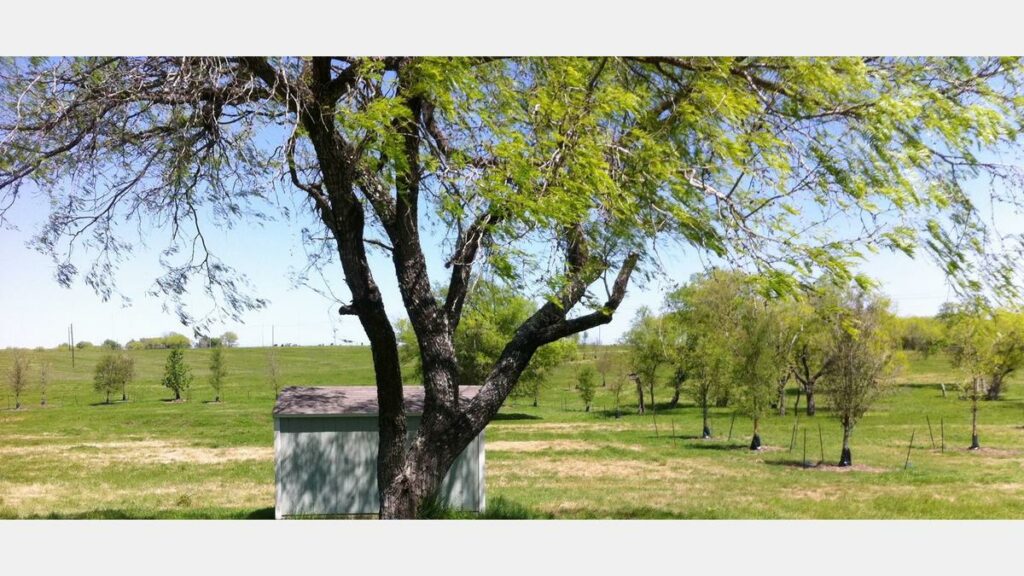

The Mission Reach Ecosystem Restoration and Recreation Project has increased the quality, quantity and diversity of plants and animals (flora and fauna) along the eight miles of the San Antonio River Mission Reach area. The ecosystem restoration process was accomplished by restoring the natural pool, riffle, run sequences; reconnection of two historic river remnants; restoration of natural backwater habitats; and restoration of the native riparian corridor, including the planting of over 20,000 young trees.

The Mission Reach looks much different than the historic San Antonio River Walk and the Museum Reach area of the river north of downtown. The native landscape looks wild rather than manicured. Grasses and wildflowers are allowed to grow to their natural heights rather than mowed. Boat traffic on the river is limited to canoes and kayaks rather than barges. The result is a serene, natural landscape where visitors can enjoy the inherent beauty of the river.

It will take many years for the trees and vegetation to fully mature. So much of the landscape is still in its infancy. It will take approximately 50 years for the entire ecosystem restoration process to be completed.

The Mission Reach project restores two types of habitats: riparian woodland habitat and aquatic habitat.

RIPARIAN WOODLAND RESTORATION

The Mission Reach project includes the restoration of approximately 334 acres of riparian woodland habitat. This includes the planting of over 20,000 young trees and shrubs, 39 native tree and shrub species and over 60 native grass and wildlife species. The Mission Reach project was designed to mimic the diversity and density of a naturally occurring riparian area that exists during drought and flood conditions. Trees were planted approximately two years after the completion of each phase of the Mission Reach in order to give time for the vegetation and grasses to become established. Just like the Eagleland Segment, it is hard work to maintain these areas while the native plant communities grow and spread. For example, during one week in August 2010, over 3 tons of weeds and weed seeds were hand pulled from the area.

AQUATIC HABITAT RESTORATION

Previous flood control efforts had channelized the Mission Reach and eliminated many of the features that allow for a diverse river ecosystem to thrive, but the SARIP helped to revitalize this incredible aquatic habitat. River restoration was accomplished by restoring natural river features to 113 acres along the river such as riffles, runs, pools, and embayments (oxbow lakes). Each of these elements of the river provide different types of habitat to maintain a diverse and healthy aquatic ecosystem.

- A riffle appears as shallow choppy water as it quickly bubbles over rocks. This action brings oxygen into the river for aquatic species and provides valuable habitat for insects and small fish.

- A run is generally a larger area of average depth and velocity. Riffles and runs will lead to larger areas of deep, slow moving water called pools.

- Pools provide an area for the sediment in a river to deposit and provide valuable habitat during times of low water where larger species of fish can reside.

- Embayments form naturally as bends in the river become crescent-shaped bodies of still water. These areas provide habitat for plants and animals that do not thrive in the flowing water of the river, while also helping to process and filter floodwaters before they move into the river.

RESTORING HISTORICAL CONNECTIONS

The Mission Reach segment consists of Mission Portals that reconnect the river to the four Spanish missions that relied on it hundreds of years ago – Mission Concepcion, Mission San Jose, Mission San Juan and Mission Espada. These connections feature historic and artistic interpretations of the story of the missions and highlight their social and cultural importance to the area. The Mission Reach Project included the portals and restored two sections of the river that historically flowed past the missions in order to reinforce the relationship between the river and the missions. Project planners worked closely with the National Park Service to ensure that there was a seamless transition between the Mission Reach and the San Antonio Missions National Historic Park so visitors could experience the rich history of the area.

Digital Archives

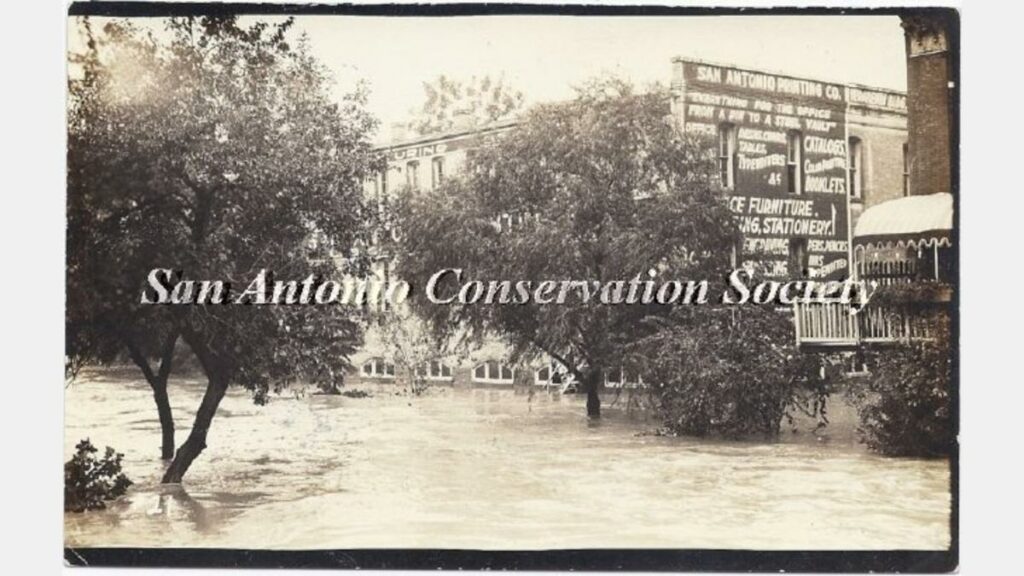

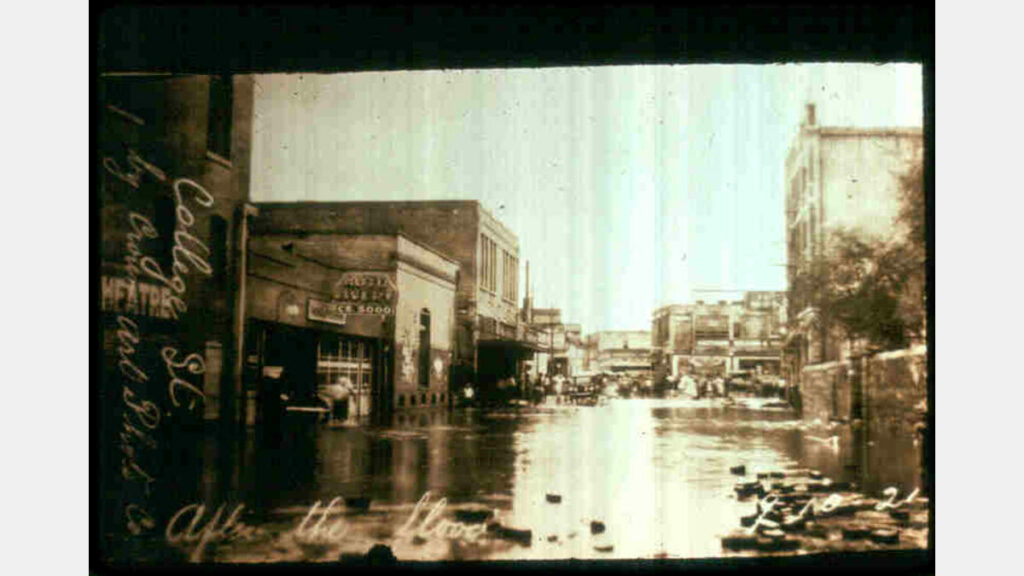

The San Antonio River Authority (River Authority) contracted with the University of Texas as San Antonio (UTSA) to house its archive at the Special Collections of the UTSA Libraries to help commemorate the agency’s 75th Anniversary and to make the agency’s archive materials easy to access by the public. Historical research materials in the collection include photographs and documentation of the flood of 1921, as well as reports, project materials, blue prints, correspondence, maps, surveys, minutes, photographs, newspaper clippings and publications, including River Authority newsletters, magazines and brochures. The River Authority’s oral history collection is also housed within the archives at UTSA. The oral history collection is made up of over 30 recordings made by River Authority board and staff, as well as key stakeholders, all sharing their institutional knowledge about specific past and present River Authority projects. The River Authority’s archive program is continuous and is updated every six months.

The River Authority’s online finding aid and digital collections can be found at the Special Collections of the UTSA Libraries or by visiting:

San Antonio Channel Improvements Project

Flooding has plagued the San Antonio River Basin for generations. As recent as 2015, this region has experienced major flooding. Its effects, flooding in the Upper San Antonio River watershed, are typically felt throughout Bexar, Wilson, Karnes and Goliad counties. Since its creation in 1937, the San Antonio River Authority (River Authority) has been a leader among government agencies developing flood control solutions within the basin.

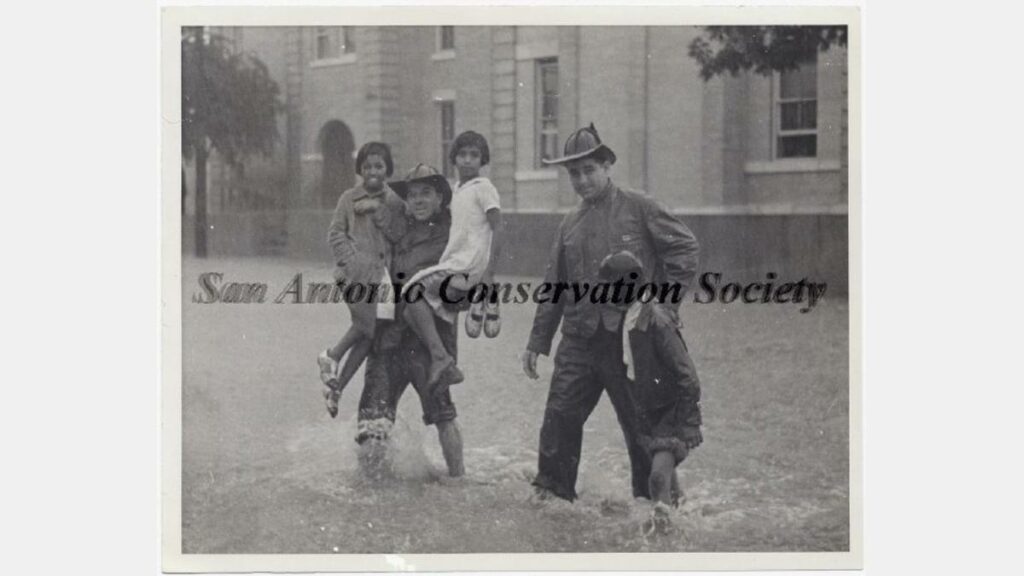

Following a devastating flood in 1946, River Authority began working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (COE) and the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), to develop strategies that address flooding in and along the San Antonio River and its tributaries.

In 1954, the U.S. Congress authorized the COE to construct the San Antonio Channel Improvements Project (SACIP). The River Authority continues to serve as the local sponsor with the COE on projects throughout the Basin. The River Authority formed important partnerships with local governments, including the Escondido Watershed District in Karnes County, Bexar County and the City of San Antonio, to implement significant flood control projects.

Through the SACIP, the River Authority has worked with the COE on major realignment and channelization to 31 miles of the San Antonio River and its tributaries, which continue to provide invaluable flood protection. Two underground tunnels, one at the San Antonio River and the other at San Pedro Creek, also divert floodwaters from San Antonio’s central government and business districts. These improvements serve as the backbone for our community’s floodwater conveyance system and protected San Antonio from significant loss of life and property damage in the October 1998 flood.

Recent efforts have transformed and enhanced the flood carrying capacity of the River by applying modern, environmentally sensitive and aesthetic construction methods. The partnership among the River Authority, the City of San Antonio, Bexar County and the COE, wanted to facilitate a steady flow of water downstream, while constructing recreational amenities and improvements from Brackenridge Park, south to Mission Espada. A 22-member citizen committee was appointed by the partnership in 1998 to guide the planning and implementation of this major community project. This project, known as the San Antonio River Improvements Project, was completed in October of 2013. Throughout its development and construction, the River Authority served as project manager and administrator for the COE, Bexar County and the City of San Antonio partnership.

San Antonio River Milestones

1700s

First acequia is completed drawing water from San Pedro Springs.

Mission San Antonio de Valero moves to second location on east side of San Antonio River at the northeast corner of present La Villita area.

Zacatecan Mission San José y San Miguel de Aguayo de Buena Vista is founded by Fray Antonio Margil de Jesús a few miles south of Mission San Antonio de Valero east of San Antonio River.

San Pedro Springs Park set aside as a public space by Spanish decree, making it today, the sixth oldest park in the United States.

“Spanish Governor’s Palace” is built near San Pedro Creek within the Presidio. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP).

1800s

In a written report by Antonio Martinez, Gov. of Province of Béjar announces that San Antonio has suffered much damage and loss of life at the hands of a great rain and the flood of water from the San Pedro Creek and San Antonio River. Many homes have been swept away and many citizens have been left destitute.

Texas officially is admitted as a State into the United States.

San Antonio River and area creeks flood. Following the flood, the first proposal was made to build a dam near the headwaters of the San Antonio River at the end of Olmos Creek.

City Council takes official action to reserve a clearly defined area for San Pedro Springs Park. The San Antonio Daily Ledger reported: A public square embracing an extent of fifty acres, has been set apart, above our town. From the heart of this square, leap forth, from God’s alembic, the clear waters of San Pedro.

Texas secedes from the U.S.

George Brackenridge purchases 217 acres of land, including the headwaters of the San Antonio River.

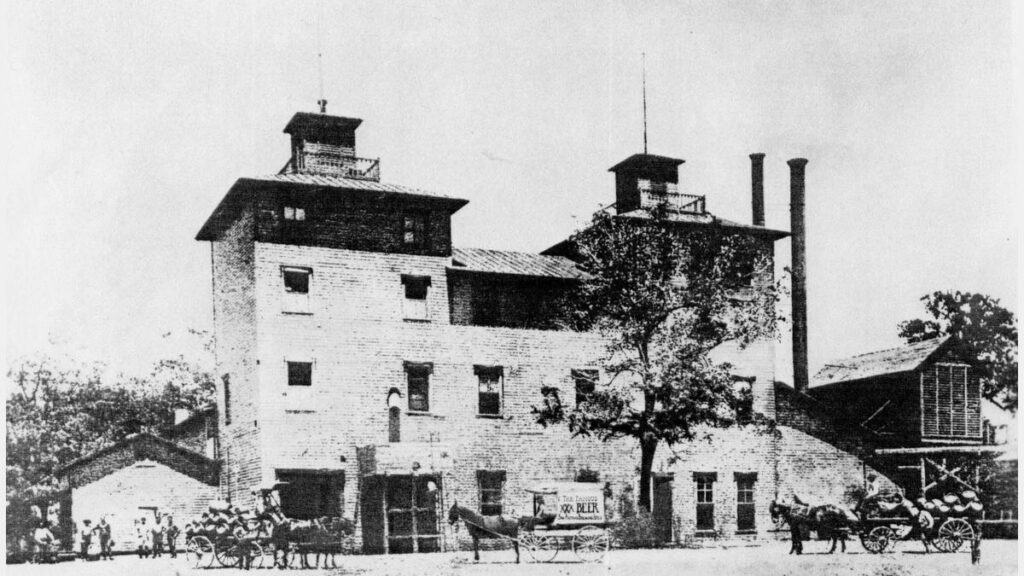

The City Brewery, later to be known as the Pearl Brewing Company, opens on the San Antonio River.

The Hot Sulphur Wells Hotel (Hot Wells Resort) opens near the San Antonio River and becomes the crown jewel of the South Side. The spa resort remained open for four decades and hosted a variety of celebrities over the years including Will Rogers, Cecil B. DeMille, Douglas Fairbanks, Charlie Chaplain and Teddy Roosevelt.

The San Antonio River and area creeks flood.

1900s

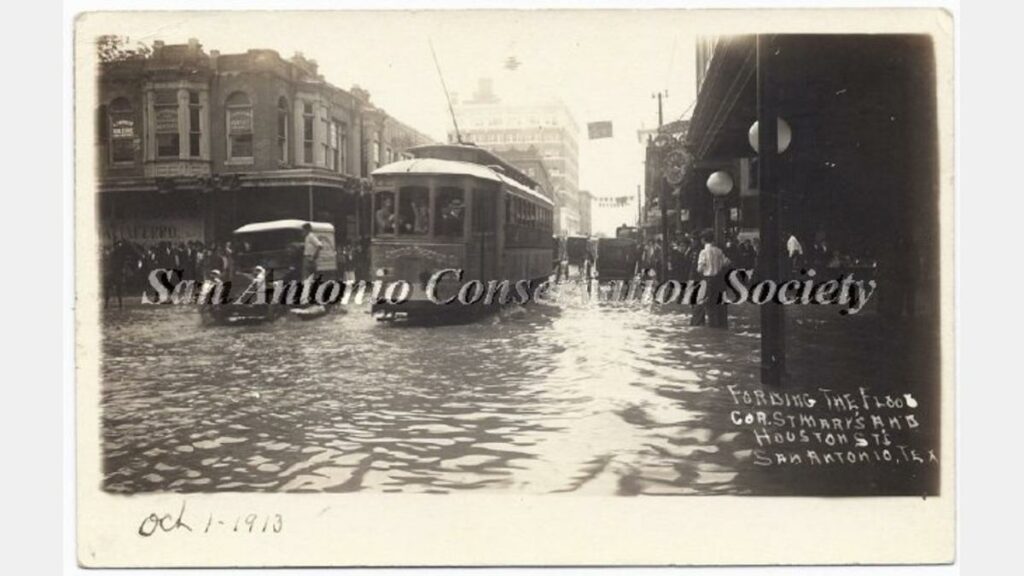

A record rainfall of over 7 inches in 24-hours caused major flooding along the San Antonio River, San Pedro Creek and Alazán creeks. Four lives were lost and significant damage occurred in downtown San Antonio estimated at $250,000 (almost $6.2 million in 2017 dollars).

Another major flood hit central and south Texas, including the loss of one life in San Antonio and approximately $50,000 of damage in downtown San Antonio (estimated $1.2 million in 2017 dollars).

San Antonio historic flood kills 51 people and causes $3.7 million dollars in damages (over $52.1 million in 2017 dollars). The 7.38 inches officially recorded in San Antonio combined with amounts twice as heavy from higher ground to the north, sent a massive surge of water down the San Antonio River. All but four of the deaths occurred along the San Pedro and Alazán creeks.

Following a storm, the Olmos Dam proved its worth by holding back 20 feet of water.

Texas Centennial is celebrated with a River Parade. (Photo credit: Visit San Antonio)

Texas Cavaliers First River Parade - The Texas Cavaliers sponsor their first Fiesta night parade on the San Antonio River Walk attracting an estimated 50,000 people to the river. (Photo credit: Fiesta San Antonio)

The San Antonio River and area creeks flood resulting in the loss of four lives.

As a result of the flood of 1946, the U.S. Congress authorized the San Antonio River Channel Improvements Project (SACIP) allowing Bexar County and the San Antonio River Authority (River Authority) to enter into a partnership with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to improve flood control along 31 miles of the San Antonio River and its tributaries. This involved realignment and channelization of the river system to move flood waters quickly away from urbanized areas. Construction began on the SACIP in 1958.

Nine dams along Calaveras Creek (Bexar County) and eleven along Escondido Creek (Karnes County) were completed and plans were underway for additional dams along Martinez Creek and Salado Creek (both in Bexar County).

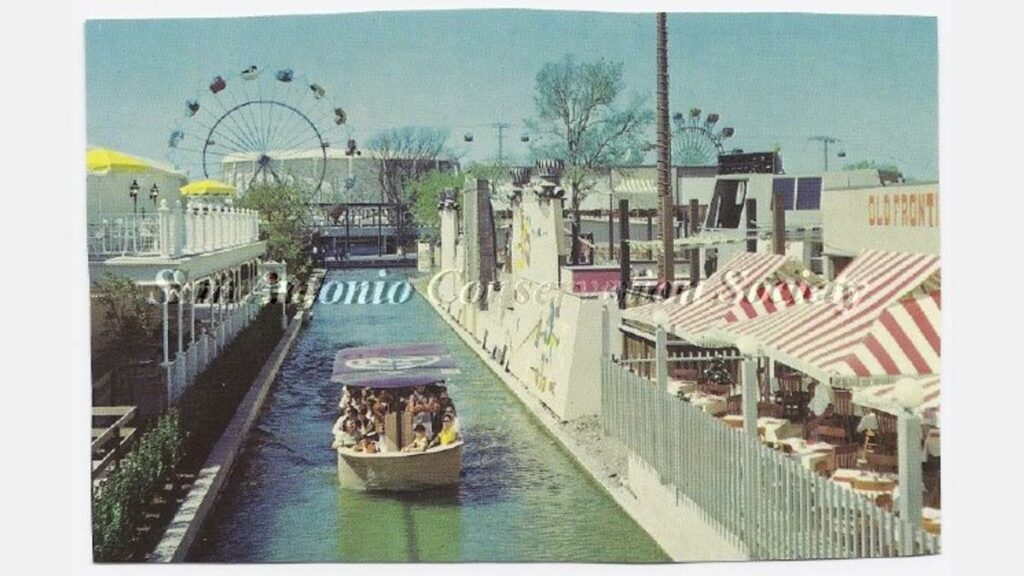

“HemisFair 1968” opens on April 6.

A major River Walk improvement south toward the King William Historic District was completed by Bexar County, the San Antonio River Authority and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The project garnered the Chief of Engineers’ 1971 National Award of Merit for General Landscape Development.

William W. McCormick, president of Joske’s Department Store, in an effort to get shoppers to come back downtown, credited with convincing the city to install the now famous tradition of putting holiday lights in the trees along the River Walk. Today, the annual holiday river parade, which takes place on the Friday following Thanksgiving, is televised live and is syndicated for broadcast in over 120 U.S. markets.

The City reorganized its water department into a new agency named the San Antonio Water System (SAWS).

Completion of the San Antonio River Flood Tunnel designed to work with the Olmos Dam to protect downtown San Antonio from damage.

2000s

Congressional approval is obtained to include environmental restoration and recreation as project purposes which opened the door for the development of the Mission Reach Ecosystem Restoration and Recreation Project as part of the San Antonio River Improvements Project.

Devastating floods hit the San Antonio River and area creeks.

The Downtown Segment (from Houston St. to Lexington Ave.) of the San Antonio River Improvements Project was completed and was recognized with a historic preservation award from the San Antonio Conservation Society and the Downtown Alliance’s Downtown Best award for the Best Arts & Culture Project.

The Bexar Regional Watershed Management (BRWM) partnership was created which brings the San Antonio River Authority together with the City of San Antonio, Bexar County and 20 suburban cities within Bexar County to work cooperatively on water quantity and quality issues.

The 6.6 mile Goliad Paddling Trail in Goliad County officially recognized by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Museum Reach Grand Opening.

Branch River Park on the San Antonio River Opens.

The John William Helton – San Antonio River Nature Park opens in Wilson County.

The 12 mile Saspamco Paddling Trail in Bexar and Wilson counties officially recognized by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Planning begins for a linear trail park along the Escondido Creek in Kenedy.

Graytown Park on the San Antonio River opens in Wilson County.

San Antonio Missions designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The 8 mile Mission Reach Paddling Trail in Bexar County officially recognized by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Work begins to restore the Hot Wells Resort along the Mission Reach Ecosystem and Recreation Project. The nonprofit Hot Wells Conservancy will oversee programming for the park and raise funds for future improvements, including renovation of a three-story wing of the bathhouse for a museum, office and meeting space.

The San Antonio River Authority commemorated the fifth anniversary of the grand opening of the Mission Reach Ecosystem & Recreation Project with a photo contest to encourage the public to visit the segment and submit pictures in several categories for a chance to win prizes with an emphasis of outdoor recreation.

The Mission Reach Flotilla Fiesta becomes an official Fiesta San Antonio event. The event, in partnership with the San Antonio River Foundation, is designed to bring awareness to the Mission Reach Ecosystem Restoration and Recreation Project on the San Antonio River.

Escondido Creek Grand Opening.

THIESS International Riverprize

On September 19, 2017 at the River Symposium and Environmental Flows Conference in Brisbane, Australia, the San Antonio River was recognized by the International RiverFoundation as the recipient of this year’s Thiess International Riverprize Award.

The Theiss International Riverprize, presented by the International RiverFoundation, is the world’s foremost award in river basin management. It recognizes and rewards organizations making waves in the sustainable management of the world’s rivers, whether at the grassroots or transboundary level. The prize rewards inspiring initiatives that demonstrate Integrated River Basin Management to restore and protect rivers, wetlands, lakes and estuaries.

The San Antonio River was recognized in part for the having invested $530 million on improvements which include the San Antonio River Improvements Project (SARIP) which added flood management, amenities, ecosystem restoration and recreational improvements to over 13 miles of the San Antonio River. The famous 15-mile San Antonio River Walk – a world-leading example of inspiring urban park design and prosperous riverfront development was also highlighted for connecting over 2,000 acres of public park land and attracting over 11.5 million visitors annually, pumping $3.1 billion into the local economy. The work to improve water quality throughout the entire basin was also mentioned as a contributing factor in the selection process.

The San Antonio River was one of four finalists in the 2017 Thiess International Riverprize, facing close competition from Alaska’s Nushagak and Kvichak Rivers, the United Kingdom’s River Tweed, and the Pasig River in the Philippines. Past winners include the Niagara River, Lake Eyre Basin and the Rhine River. Visit the International RiverFoundation for more information about the International Riverprize award.

Museum Reach 10-Year Anniversary

The San Antonio River Walk Museum Reach celebrated its 10 year anniversary in 2019. From the unique culinary and cultural experiences of Pearl to the vibrant Tobin Center for the Performing Arts, the Museum Reach has created a space for outdoor recreation, urban living, phenomenal restaurants and bars, lively entertainment and thriving businesses.

Economic data gathered by the San Antonio River Authority indicates that in the first 10 years of the Museum Reach Urban Segment, the $72 million public investment in the river served as a catalyst to return nearly $2 billion in construction investment from Lexington Ave. to Hildebrand Ave., so the project actually stimulated far more investment than what was projected for in the 2007 construction estimate, and it did so in less than 10 years, which is a shorter horizon than the 2007 study predicted. Other economic points of interest: Land values between Lexington and Josephine St. have increased over 270% since 2009; Over 3500 housing units have been developed; Over 2,100,000 sq ft of office space and retail space has been developed.

The San Antonio River Authority installed a trail counter along the Museum Reach near the lock and dam in June 2014. It counts both pedestrians and cyclists and determines if they are going north or south. As of May 2019, it has counted a sum of northbound and southbound foot traffic equaling 1,009,804 counts and 128,912 cyclist counts for a total count of both pedestrian and cyclists of 1,138,716.

If you have not experienced the Museum Reach section of the San Antonio River Walk, we encourage you to find time to visit some of the flourishing businesses and artwork along the trail.

Fun Facts

Zachry Construction Corporation was the contractor hired to construct the Museum Reach.

The Museum Reach Urban Segment design is broken down into three historical themes:

- the Hugman theme, from Lexington Avenue to just upstream of 9th Street, reflects the use of limestone on the original River Walk;

- the San Antonio Museum of Art theme, from 9th Street to I-35, reflects the use of brick on the San Antonio Museum of Art; and

- the Pearl theme, from I-35 to Josephine Street, reflects the industrial aesthetic of the Pearl through the use of sandblasted concrete.

The river bottom of the Museum Reach Urban Segment is made of large cobble (approximately 6” diameter rocks) to provide a more natural environment for aquatic life. Low Water Fish Sanctuaries are portions of the riverbed that were excavated to create pools where fish can survive when the river is drained for maintenance and repairs. Also to protect aquatic wildlife, fish lunkers, which are essentially concrete boxes, were recessed into the river bulkheads to provide shelter for aquatic life from sun and strong currents.

CFZ Group, L.L.C. was the landscape architect for the Museum Reach Urban Segment. The project design featured over 100 plant species, mostly native grasses, shrubs and trees, with a few select non-natives such as palm trees (a unifying feature from the original Hugman River Walk design).

The Hugman Dam, just upstream of Lexington Avenue, was kept as a historical feature of the Urban Segment. The dam is named after River Walk architect Robert H.H. Hugman as it was designed by him and installed in the river around 1940 as the northern boundary of the original River Walk. A third of the dam has been removed to allow barge traffic through. Nearby signage gives the history of Hugman and the dam.

The Alamo Mills Dam was discovered during construction near VFW Post 76 just downstream of Jones Ave. The dam was built in the 1870s and was partially dismantled in the early 1900s. Subsequently, the dam was silted over and lost to history until the Museum Reach Urban Segment construction crews found it. The dam was used to send water through a mill raceway to the Alamo Mill at 8th The mill made flour and, later, ice. During construction of the Museum Reach, the dam was made to be visible to visitors day and night, and signage gives its history.

Current (2019) annual funding from the San Antonio River Authority for the operations and maintenance of the Museum Reach is $1.4 million.

Project Timeline

A joint planning effort by six local government entities resulted in the River Corridor Feasibility Study. The study’s “River Corridor Plan” provided a conceptual plan for improvements along the San Antonio River from Hildebrand to I.H. 10 through downtown San Antonio.

Why this is important: While the design and development of the Museum Reach did not formally begin until the 1990s, it is worth noting that visionaries, like Lila Cockrell, were studying the feasibility of expanding the River Walk northward in the early 1970s.

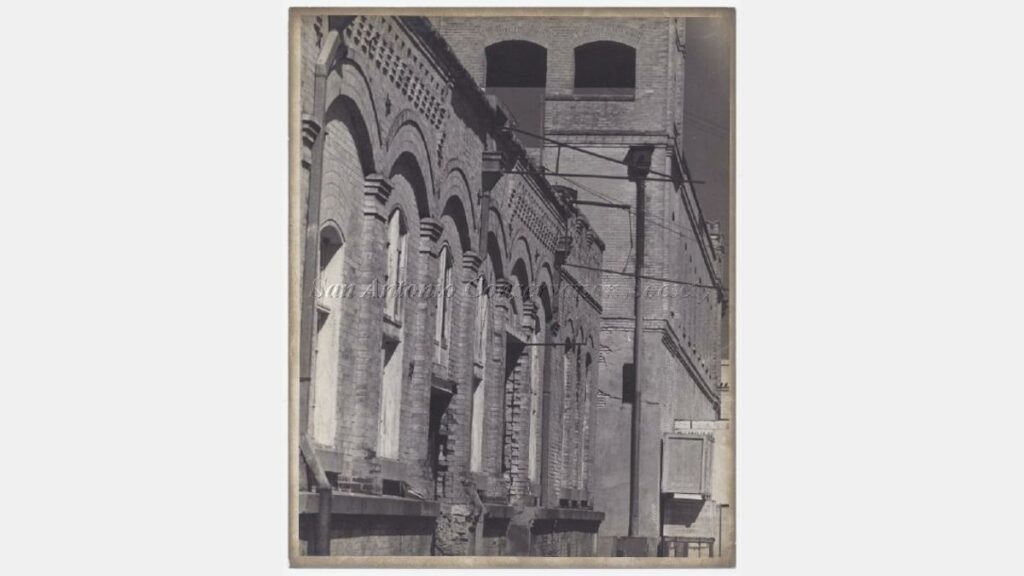

San Antonio Museum of Art opens on the banks of the San Antonio River in a re-purposed Lone Star Brewery after a $7.2 million adaptive renovation.

Why this is important: The river was not a feature of the San Antonio Museum of Art as it is today because until completion of the Museum Reach, the river behind the museum was essentially a forgotten drainage ditch.

Completion of the San Antonio River Flood Tunnel designed to work with the Olmos Dam to protect downtown San Antonio from damage. The project includes an inlet facility located at Josephine Street and the San Antonio River, a 24-foot diameter, 3-mile long tunnel and an outlet site at Lone Star Boulevard. Ten months after completion of the tunnel, on October 17-18, 1998, south central Texas experienced record-breaking rainfall, and both the San Pedro Creek and the San Antonio River tunnels performed as designed, sparing downtown San Antonio from a devastating flood. In 1999, the tunnel project won the State of Texas Outstanding Civil Engineering Achievement Award from the American Society of Civil Engineers; it also received a national-level Award of Merit. A year later, it was one of four projects to receive the Federal Design Achievement Award from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), as well as an achievement award from the American Society of Civil Engineers in recognition of the San Antonio River Tunnel Inlet Site.

Why this is important: The completion of the flood tunnel was important not only for the protection it provides downtown San Antonio, but it also provided the ability to safely expand the River Walk northward into the Museum Reach area. The tunnel also allowed the San Antonio River Authority to drain the river in the Museum Reach area during construction of the Museum Reach, which was critically important for construction costs and timeline.

Bexar County, the City of San Antonio and the San Antonio River Authority authorized the creation of a local stakeholder group to be named the San Antonio River Oversight Committee (SAROC), whose purpose was to advise the planning, design, project management, construction and construction phasing and funding for the development of flood control and amenity improvements on what would become known as the San Antonio River Improvements Project (SARIP).

Why this is important: This is the formal beginning of the SARIP, including the Museum Reach and Mission Reach projects.

SAROC completes Planning Document for the SARIP detailing the community vision for the river.

Why this is important: This document was the guiding principles throughout design and construction of the SARIP.

Draft of the SWA Concept Design completed.

Final SWA Concept Design Document completed.

Preliminary Design on Museum Reach initiated by the design team of Ford, Powell & Carson Architects & Planners and HDR Engineering, Inc.

Preliminary Design of Museum Reach completed.

Final Design of the Museum Reach: Urban Segment completed

Why this is important: During design, the Museum Reach was separated into two phases, the Urban Segment and the Park Segment. The Museum Reach “Urban Segment” was from Lexington Ave. to Josephine St. and the Museum Reach “Park Segment” was from Josephine St. to Hildebrand Ave. Today, the Museum Reach is consider one complete length from Lexington Ave. to Hildebrand Ave.

30% Final Design Documents on Museum Reach completed.

30% Cost Estimate on Museum Reach completed.

SAROC approves Public Arts Master Plan for SARIP.

50% Final Design documents on Museum Reach completed.

50% Cost Estimate for Museum Reach is completed.

90% Cost Estimate on Museum Reach Urban Segment completed.

Bexar County, City of San Antonio and the San Antonio River Authority approve SARIP Interlocal Agreement.

US Army Corps of Engineers 404 Permit for Museum Reach Urban Segment secured.

100% Cost Estimate on Museum Reach Urban Segment completed.

Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) permit for Lock and Dam secured.

An economic impact study projected $1.1 billion in new construction along the Museum Reach upon completion of the project over a 10-15 year horizon.

Construction of the Museum Reach Urban Segment of the San Antonio River Improvements Project initiated. The project costs $71.2 million and is funded by the following partners are: City of San Antonio $53.1 million; Bexar County $13.1; Private funds through the San Antonio River Foundation, $6,5 million; San Antonio Water System, $300,000 (for utility relocation); The San Antonio River Authority served at project and construction manager and agreed to take on the long-term operations and maintenance of the Museum Reach upon completion of the project.

Museum Reach Urban Segment of the San Antonio River Improvements Project opens adding nearly 1 ½ miles to the River Walk north of Lexington Ave.

Impact of the San Antonio River Walk Study released conservative conclusions that 11.5 million people visit the River Walk annually which stimulates an overall economic impact of $3.1 billion and support 31,000 jobs.

Why this is important: This study largely focused on the downtown and Museum Reach Urban Segment sections of the San Antonio River Walk and included a small amount of research on the Mission Reach.

An economic study done as part of the 5th anniversary of the Museum Reach shows the Museum Reach generates an annual economic impact from new business operations of $139 million and over $253 million in private investment has come since the project opened in 2009.

Why this is important: This study just looked at the Museum Reach Urban Segment from Lexington Ave. to Josephine St.

Construction of Museum Reach Park Segment initiated.

Between May 2007 and May 2016, staff from the San Antonio River Authority’s Intergovernmental and Community Relations Department provided and/or organized over 400 presentations and/or tours about the San Antonio River Improvements Project that were given to local, state, national and international audiences.

Why this is important: the construction of the Museum Reach and Mission Reach projects greatly increased the worldwide visibility of the San Antonio River Walk as governments and organizations from around the globe began to look to the San Antonio community for guidance in developing and restoring rivers.